Sacramento calls itself America’s Farm-to-Fork Capital, but in a few days it will take on another role—host to a Terra Madre gathering, part of the global Slow Food movement. Terra Madre is about more than cuisine; it is a philosophy that insists food is culture, biodiversity, and justice. Few American cities are better positioned to embody those values than Sacramento, a community where fertile soil, immigrant traditions, and innovation have long shaped what and how people eat.

The story begins in the region’s fields and rivers. Indigenous peoples harvested salmon, acorns, and seeds here for millennia, practicing stewardship that modern sustainability efforts echo. Later, immigrants brought their own traditions—Chinese workers reclaiming Delta land, Japanese growers introducing specialty crops, Italians planting vineyards, Portuguese tending dairies. Each added new layers of diversity to Sacramento’s food culture, a legacy still visible today at farmers’ markets where nopales sit beside bok choy, bitter melon beside basil, heirloom tomatoes beside Armenian cucumbers.

That diversity isn’t just culinary—it’s cultural memory. Each seed, recipe, and farming method tells a story of migration and adaptation. And in Sacramento, many of those traditions are still carried on by families who farm small plots and sell directly to the public. On a Saturday morning at the Midtown market, the city’s food history feels alive: children sampling stone fruit, chefs picking produce for their menus, and farmers greeting neighbors by name.

The connection between food and community extends to classrooms. School gardens across the region teach children to plant seeds, harvest vegetables, and understand the web of soil, water, and care that sustains life. These small plots are more than enrichment—they cultivate awareness of ecology and health while nurturing a sense of responsibility for the future. For many children, pulling a carrot from the earth is their first taste of food as a living system rather than a packaged product.

Yet Sacramento’s abundance is not equally shared. Food deserts persist in neighborhoods where fast-food outlets outnumber grocery stores, and many families struggle to afford fresh produce. Local organizations have stepped in with creative solutions. Alchemist CDC doubles the value of CalFresh benefits at farmers’ markets, ensuring that low-income households can stretch their food dollars. The Ujamaa Farmer Collective creates land access for Black farmers excluded from ownership for generations. Community fridges and grassroots exchanges help bridge gaps between plenty and scarcity. These efforts echo Terra Madre’s conviction that food should be a human right.

Other movements are quieter but equally powerful. Seed saving, for instance, has become a form of cultural preservation as well as agricultural resilience. Through libraries and swaps, volunteers share packets of beans, squash, and tomatoes, each one tied to the memory of who grew it before. In a city shaped by migration, preserving seeds also preserves identity.

Restaurants carry this ethos to the table. Chefs across Sacramento craft menus that highlight seasonal produce, heritage grains, and immigrant flavors. A dish might pair Lao eggplant with California olive oil or lamb with Armenian yogurt and Delta figs. Dining becomes storytelling, each plate a bridge across cultures. The city’s food festivals amplify that spirit, from the Farm-to-Fork Festival on the Tower Bridge to neighborhood harvest dinners. These events are not just about abundance—they are about gathering, sharing, and building community through food.

Sacramento is not without its contradictions. Industrial almond and rice production dominates nearby fields, consuming vast amounts of water. Farmworkers remain vulnerable to low wages and harsh conditions. Climate change brings uncertainty to harvests that once seemed dependable. But acknowledging these realities is part of the work. Terra Madre is not about romanticizing food systems; it is about facing hard truths while imagining better ones.

As Sacramento joins the Terra Madre conversation, it adds its voice to a global chorus. Around the world, Indigenous farmers are saving heritage seeds, African cooperatives are reviving ancient grains, and Mediterranean fishers are protecting fragile ecosystems. Sacramento’s contribution is a story of abundance and inequity, of immigrant resilience and innovation, of chefs and farmers who see food as both sustenance and story.

At the Midtown market, a child bites into a peach, a farmer offers a slice of melon, and a chef lingers over bunches of basil. In these simple exchanges, the essence of Terra Madre is already present—diverse, sustainable, rooted, and shared. Sacramento may call itself the Farm-to-Fork Capital, but as it welcomes Terra Madre, it also claims a larger role: a city where food connects local lives to a global table.

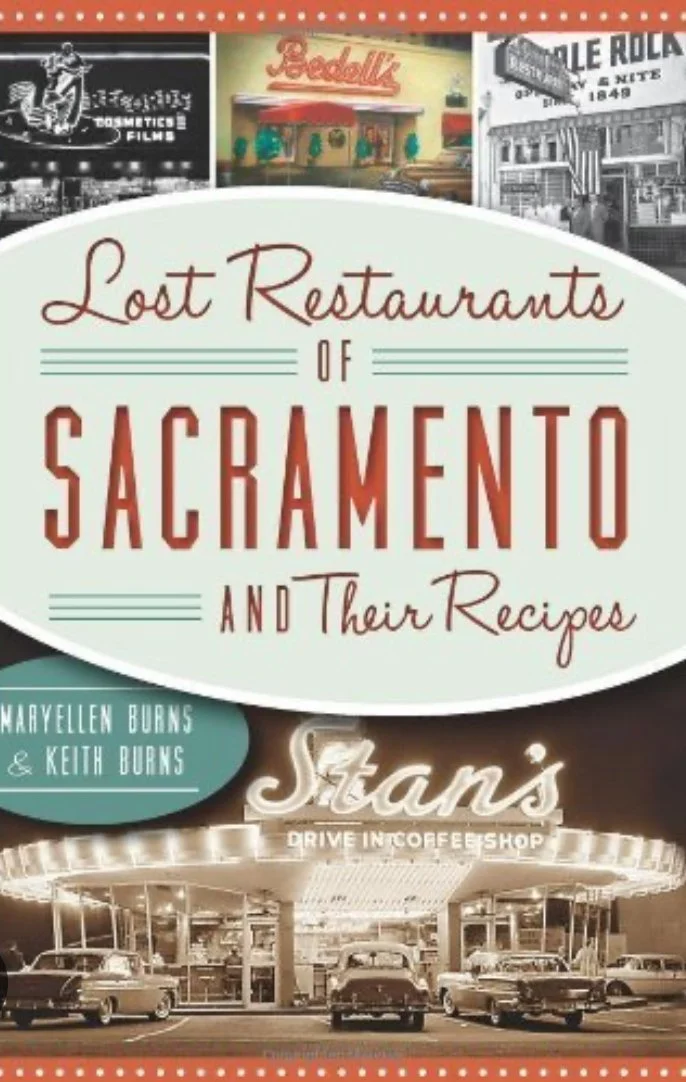

Maryellen Burns is a Sacramento-based author, cultural historian, and culinary storyteller whose work explores the deep connections between food, memory, and place. She is the author of Lost Restaurants of Sacramento and Their Recipes, The Foods We Share. The Stories We Tell, and more than a half dozen other titles. A member of Les Dames d'Escoffier, Slow Food Sacramento, and the Bay Area Culinary Historians, she champions regional foodways, immigrant traditions, and community narratives through books, exhibits, and public programs across the country.