There Was a Time When All Food Was Slow

Maryellen Burns

Before drive-thrus, microwaves, and meal kits, food took time. It simmered in pots, rose in bread pans, or smoked gently over outdoor fires. Ingredients were gathered by hand or grown from the soil outside the kitchen door. Even the act of eating was slow — a family, a table, a ritual.

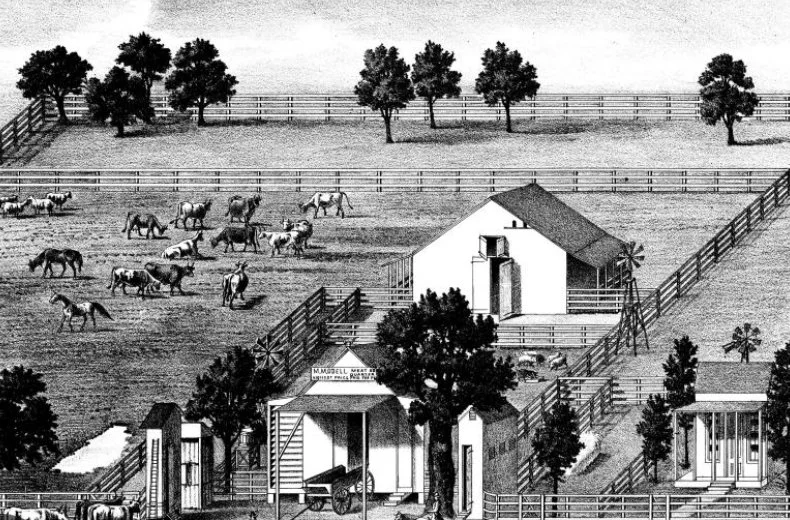

Sacramento, long before it became a hub for fast-casual dining and food trucks, was a place where food was inherently slow. From the Indigenous communities who harvested acorns, fish, and native plants with precision and care, to Gold Rush-era settlers who cultivated heirloom crops and raised livestock, food was seasonal, local, and shared.

Today, the Slow Food movement reminds us of what we once knew instinctively: that good, clean, and fair food connects us to the land, to tradition, and to each other.

The Slow Food movement began in the 1980s in Italy when a group of activists, led by Carlo Petrini, protested the opening of a McDonald’s near the Spanish Steps in Rome. Their message was simple but revolutionary: food is culture, not commodity. What we eat reflects who we are, where we live, and what we value.

That message traveled across oceans and found fertile ground in cities like Sacramento — a place that has always been deeply tied to agriculture and community. Here, the values of the movement resonated with chefs, farmers, educators, and everyday home cooks who understood that slowing down could help us reclaim something precious.

Sacramento’s Naturally Slow Roots

Sacramento is often dubbed "America’s Farm-to-Fork Capital," and for good reason. The region is one of the most agriculturally rich in the country. But before it was branded, Sacramento was already a slow food city.

Local Chinese, Japanese, Italian, Portuguese, Filipino, and Mexican communities brought with them long traditions of preserving, fermenting, drying, and home gardening. Victory gardens thrived during wartime. Backyard fruit trees lined entire neighborhoods. Family recipes were passed down not in cookbooks but in conversation.

Long before the movement had a name, Sacramento lived its values. During the early 20th century, families canned peaches and tomatoes. Neighborhoods hosted block parties where dishes reflected heritage — Filipino adobo, Italian sausage, Japanese pickles, Portuguese sweet bread. Gardens grew out of necessity and pride.

Canneries like Libby, McNeill & Libby and Del Monte allowed for large-scale preservation, but even that was rooted in the idea of food’s future — of saving the harvest for the months ahead. Sacramento’s food history is a story of hands, soil, time, and taste.

And while modern life has hurried much of our eating habits, the heart of slow food persists here.

Slowing Down

In a world that constantly accelerates, there’s something radical about slowing down. Taking time to cook a pot of beans. Baking bread from a recipe scribbled in your grandmother’s hand. Saving seeds from last year’s tomato harvest. These acts, though simple, carry weight. They connect us not just to food, but to people — the ones who came before and those who will come after.

Sacramento is changing fast. But in the quiet spaces — a neighbor exchanging figs over the fence, a garden sprouting in a schoolyard, a community potluck under string lights — the old ways persist. Not as nostalgia, but as continuity.

There was a time when all food was slow. And in Sacramento, if you know where to look, it still is.

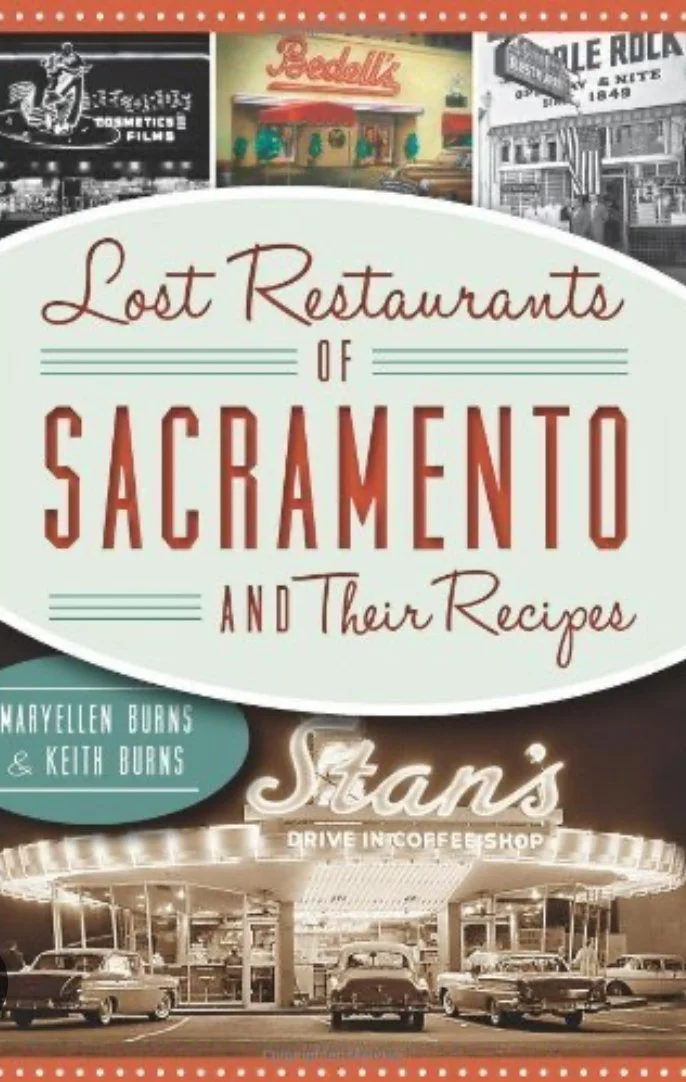

Maryellen Burns is a Sacramento-based author, cultural historian, and culinary storyteller whose work explores the deep connections between food, memory, and place. She is the author of Lost Restaurants of Sacramento and Their Recipes, The Foods We Share. The Stories We Tell, and more than a half dozen other titles. A member of Les Dames d'Escoffier, Slow Food Sacramento, and the Bay Area Culinary Historians, she champions regional foodways, immigrant traditions, and community narratives through books, exhibits, and public programs across the country.